Philippine History

Early History -The Negritos are believed to have migrated to the Philippines some 30,000 years ago from Borneo, Sumatra, and Malaya. The Malayans followed in successive waves. These people belonged to a primitive epoch of Malayan culture, which has apparently survived to this day among certain groups such as the Igorots. The Malayan tribes that came later had more highly developed material cultures. In

the 14th cent. Arab traders from Malay and Borneo introduced Islam into

the southern islands and extended their influence as far north as Luzon.

The first Europeans to visit (1521) the Philippines were those in the

Spanish expedition around the world led by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand

Magellan. Other Spanish expeditions followed, including one from New

Spain (Mexico) under López de Villalobos, who in 1542 named the islands

for the infante Philip, later Philip II.

In

the 14th cent. Arab traders from Malay and Borneo introduced Islam into

the southern islands and extended their influence as far north as Luzon.

The first Europeans to visit (1521) the Philippines were those in the

Spanish expedition around the world led by the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand

Magellan. Other Spanish expeditions followed, including one from New

Spain (Mexico) under López de Villalobos, who in 1542 named the islands

for the infante Philip, later Philip II.Spanish Control - The conquest of the Filipinos by Spain did not begin in earnest until 1564, when another expedition from New Spain, commanded by Miguel López de Legaspi, arrived. Spanish leadership was soon established over many small independent communities that previously had known no central rule. By 1571, when López de Legaspi established the Spanish city of Manila on the site of a Moro town he had conquered the year before, the Spanish foothold in the Philippines was secure, despite the opposition of the Portuguese, who were eager to maintain their monopoly on the trade of East Asia.

Manila repulsed the attack of the Chinese pirate Limahong in 1574. For centuries before the Spanish arrived the Chinese had traded with the Filipinos, but evidently none had settled permanently in the islands until after the conquest. Chinese trade and labor were of great importance in the early development of the Spanish colony, but the Chinese came to be feared and hated because of their increasing numbers, and in 1603 the Spanish murdered thousands of them (later, there were lesser massacres of the Chinese).

The Spanish governor, made a viceroy in 1589, ruled with the advice of the powerful royal audiencia. There were frequent uprisings by the Filipinos, who resented the encomienda system. By the end of the 16th cent. Manila had become a leading commercial center of East Asia, carrying on a flourishing trade with China, India, and the East Indies. The Philippines supplied some wealth (including gold) to Spain, and the richly laden galleons plying between the islands and New Spain were often attacked by English freebooters. There was also trouble from other quarters, and the period from 1600 to 1663 was marked by continual wars with the Dutch, who were laying the foundations of their rich empire in the East Indies, and with Moro pirates. One of the most difficult problems the Spanish faced was the subjugation of the Moros. Intermittent campaigns were conducted against them but without conclusive results until the middle of the 19th cent. As the power of the Spanish Empire waned, the Jesuit orders became more influential in the Philippines and acquired great amounts of property.

Revolution, War, and U.S. Control - It was the opposition to the power of the clergy that in large measure brought about the rising sentiment for independence. Spanish injustices, bigotry, and economic oppressions fed the movement, which was greatly inspired by the brilliant writings of José Rizal. In 1896

revolution began in the province of Cavite, and after the execution

of Rizal that December, it spread throughout the major islands. The

Filipino leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, achieved considerable success before

a peace was patched up with Spain. The peace was short-lived, however,

for neither side honored its agreements, and a new revolution was brewing

when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898.

revolution began in the province of Cavite, and after the execution

of Rizal that December, it spread throughout the major islands. The

Filipino leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, achieved considerable success before

a peace was patched up with Spain. The peace was short-lived, however,

for neither side honored its agreements, and a new revolution was brewing

when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898.After the U.S. naval victory in Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey supplied Aguinaldo with arms and urged him to rally the Filipinos against the Spanish. By the time U.S. land forces had arrived, the Filipinos had taken the entire island of Luzon, except for the old walled city of Manila, which they were besieging. The Filipinos had also declared their independence and established a republic under the first democratic constitution ever known in Asia. Their dreams of independence were crushed when the Philippines were transferred from Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1898), which closed the Spanish-American War.

In Feb., 1899, Aguinaldo led a new revolt, this time against U.S. rule. Defeated on the battlefield, the Filipinos turned to guerrilla warfare, and their subjugation became a mammoth project for the United States—one that cost far more money and took far more lives than the Spanish-American War. The insurrection was effectively ended with the capture (1901) of Aguinaldo by Gen. Frederick Funston, but the question of Philippine independence remained a burning issue in the politics of both the United States and the islands. The matter was complicated by the growing economic ties between the two countries. Although comparatively little American capital was invested in island industries, U.S. trade bulked larger and larger until the Philippines became almost entirely dependent upon the American market. Free trade, established by an act of 1909, was expanded in 1913.

When the Democrats came into power in 1913, measures were taken to effect a smooth transition to self-rule. The Philippine assembly already had a popularly elected lower house, and the Jones Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1916, provided for a popularly elected upper house as well, with power to approve all appointments made by the governor-general. It also gave the islands their first definite pledge of independence, although no specific date was set.

When the Republicans regained power in 1921, the trend toward bringing Filipinos into the government was reversed. Gen. Leonard Wood, who was appointed governor-general, largely supplanted Filipino activities with a semimilitary rule. However, the advent of the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s and the first aggressive moves by Japan in Asia (1931) shifted U.S. sentiment sharply toward the granting of immediate independence to the Philippines.

The Commonwealth - The Hare-Hawes Cutting Act, passed by Congress in 1932, provided for complete independence of the islands in 1945 after 10 years of self-government under U.S. supervision. The bill had been drawn up with the aid of a commission from the Philippines, but Manuel L. Quezon, the leader of the dominant Nationalist party, opposed it, partially because of its threat of American tariffs against Philippine products but principally because of the provisions leaving naval bases in U.S. hands. Under his influence, the Philippine legislature rejected the bill. The Tydings-McDuffie Independence Act (1934) closely resembled the Hare-Hawes Cutting Act, but struck the provisions for American bases and carried a promise of further study to correct “imperfections or inequalities.”

The Philippine legislature ratified the bill; a constitution, approved by President Roosevelt (Mar., 1935) was accepted by the Philippine people in a plebiscite (May); and Quezon was elected the first president (Sept.). When Quezon was inaugurated on Nov. 15, 1935, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was formally established. Quezon was reelected in Nov., 1941. To develop defensive forces against possible aggression, Gen. Douglas MacArthur was brought to the islands as military adviser in 1935, and the following year he became field marshal of the Commonwealth army.

World War II - War came suddenly to the Philippines on Dec. 8 (Dec. 7, U.S. time), 1941, when Japan attacked without warning. Japanese troops invaded the islands in many places and launched a pincer drive on Manila. MacArthur’s scattered defending forces (about 80,000 troops, four fifths of them Filipinos) were forced to withdraw to Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor Island, where they entrenched and tried to hold until the arrival of reinforcements, meanwhile guarding the entrance to Manila Bay and denying that important harbor to the Japanese. But no reinforcements were forthcoming. The Japanese occupied Manila on Jan. 2, 1942. MacArthur was ordered out by President Roosevelt and left for Australia on Mar. 11; Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright assumed command.

The besieged U.S.-Filipino army on Bataan finally crumbled on Apr. 9, 1942. Wainwright fought on from Corregidor with a garrison of about 11,000 men; he was overwhelmed on May 6, 1942. After his capitulation, the Japanese forced the surrender of all remaining defending units in the islands by threatening to use the captured Bataan and Corregidor troops as hostages. Many individual soldiers refused to surrender, however, and guerrilla resistance, organized and coordinated by U.S. and Philippine army officers, continued throughout the Japanese occupation.

Japan’s efforts to win Filipino loyalty found expression in the establishment (Oct. 14, 1943) of a “Philippine Republic,” with José P. Laurel, former supreme court justice, as president. But the people suffered greatly from Japanese brutality, and the puppet government gained little support. Meanwhile, President Quezon, who had escaped with other high officials before the country fell, set up a government-in-exile in Washington. When he died (Aug., 1944), Vice President Sergio Osmeña became president. Osmeña returned to

the Philippines with the first liberation forces, which surprised the

Japanese by landing (Oct. 20, 1944) at Leyte, in the heart of the islands,

after months of U.S. air strikes against Mindanao. The Philippine government

was established at Tacloban, Leyte, on Oct. 23.

the Philippines with the first liberation forces, which surprised the

Japanese by landing (Oct. 20, 1944) at Leyte, in the heart of the islands,

after months of U.S. air strikes against Mindanao. The Philippine government

was established at Tacloban, Leyte, on Oct. 23. The landing was followed (Oct. 23–26) by the greatest naval engagement in history, called variously the battle of Leyte Gulf and the second battle of the Philippine Sea. A great U.S. victory, it effectively destroyed the Japanese fleet and opened the way for the recovery of all the islands. Luzon was invaded (Jan., 1945), and Manila was taken in February. On July 5, 1945, MacArthur announced “All the Philippines are now liberated.” The Japanese had suffered over 425,000 dead in the Philippines.

The Philippine congress met on June 9, 1945, for the first time since its election in 1941. It faced enormous problems. The land was devastated by war, the economy destroyed, the country torn by political warfare and guerrilla violence. Osmeña’s leadership was challenged (Jan., 1946) when one wing (now the Liberal party) of the Nationalist party nominated for president Manuel Roxas, who defeated Osmeña in April.

The Republic of the Philippines - Manuel Roxas became the first president of the Republic of the Philippines when independence was granted, as scheduled, on July 4, 1946. In Mar., 1947, the Philippines and the United States signed a military assistance pact (since renewed) and the Philippines gave the United States a 99-year lease on designated military, naval, and air bases (a later agreement reduced the period to 25 years beginning 1967). The sudden death of President Roxas in Apr., 1948, elevated the vice president, Elpidio Quirino, to the presidency, and in a bitterly contested election in Nov., 1949, Quirino defeated José Laurel to win a four-year term of his own.

The enormous task of reconstructing the war-torn country was complicated by the activities in central Luzon of the Communist-dominated Hukbalahap guerrillas (Huks), who resorted to terror and violence in their efforts to achieve land reform and gain political power. They were finally brought under control (1954) after a vigorous attack launched by the minister of national defense, Ramón Magsaysay. By that time Magsaysay was president of the country, having defeated Quirino in Nov., 1953. He had promised sweeping economic changes, and he did make progress in land reform, opening new settlements outside crowded Luzon island. His death in an airplane crash in Mar., 1957, was a serious blow to national morale. Vice President Carlos P. García succeeded him and won a full term as president in the elections of Nov., 1957.

In foreign affairs, the Philippines maintained a firm anti-Communist policy and joined the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization in 1954. There were difficulties with the United States over American military installations in the islands, and, despite formal recognition (1956) of full Philippine sovereignty over these bases, tensions increased until some of the bases were dismantled (1959) and the 99-year lease period was reduced. The United States rejected Philippine financial claims and proposed trade revisions.

Philippine opposition to García on issues of government corruption and anti-Americanism led, in June, 1959, to the union of the Liberal and Progressive parties, led by Vice President Diosdado Macapagal, the Liberal party leader, who succeeded García as president in the 1961 elections. Macapagal’s administration was marked by efforts to combat the mounting inflation that had plagued the republic since its birth; by attempted alliances with neighboring countries; and by a territorial dispute with Britain over North Borneo (later Sabah), which Macapagal claimed had been leased and not sold to the British North Borneo Company in 1878.

Marcos and After - Ferdinand E. Marcos, who succeeded to the presidency after defeating Macapagal in the 1965 elections, inherited the territorial dispute over Sabah; in 1968 he approved a congressional bill annexing Sabah to the Philippines. Malaysia suspended diplomatic relations (Sabah had joined the Federation of Malaysia in 1963), and the matter was referred to the United Nations. (The Philippines dropped its claim to Sabah in 1978.) The Philippines became one of the founding countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967. The continuing need for land reform fostered a new Huk uprising in central Luzon, accompanied by mounting assassinations and acts of terror, and in 1969, Marcos began a major military campaign to subdue them. Civil war also threatened on Mindanao, where groups of Moros opposed Christian settlement. In Nov., 1969, Marcos won an unprecedented reelection, easily defeating Sergio Osmeña, Jr., but the election was accompanied by violence and charges of fraud, and Marcos’s second term began with increasing civil disorder.

In Jan., 1970, some 2,000 demonstrators tried to storm Malacañang Palace, the presidential residence; riots erupted against the U.S. embassy. When Pope Paul VI visited Manila in Nov., 1970, an attempt was made on his life. In 1971, at a Liberal party rally, hand grenades were thrown at the speakers’ platform, and several people were killed. President Marcos declared martial law in Sept., 1972,

charging that a Communist rebellion threatened. The 1935 constitution

was replaced (1973) by a new one that provided the president with direct

powers. A plebiscite (July, 1973) gave Marcos the right to remain in

office beyond the expiration (Dec., 1973) of his term. Meanwhile the

fighting on Mindanao had spread to the Sulu Archipelago. By 1973 some

3,000 people had been killed and hundreds of villages burned. Throughout

the 1970s poverty and governmental corruption increased, and Imelda

Marcos, Ferdinand’s wife, became more influential.

charging that a Communist rebellion threatened. The 1935 constitution

was replaced (1973) by a new one that provided the president with direct

powers. A plebiscite (July, 1973) gave Marcos the right to remain in

office beyond the expiration (Dec., 1973) of his term. Meanwhile the

fighting on Mindanao had spread to the Sulu Archipelago. By 1973 some

3,000 people had been killed and hundreds of villages burned. Throughout

the 1970s poverty and governmental corruption increased, and Imelda

Marcos, Ferdinand’s wife, became more influential. Martial law remained in force until 1981, when Marcos was reelected, amid accusations of electoral fraud. On Aug. 21, 1983, opposition leader Benigno Aquino was assassinated at Manila airport, which incited a new, more powerful wave of anti-Marcos dissent. After the Feb., 1986, presidential election, both Marcos and his opponent, Corazon Aquino (the widow of Benigno), declared themselves the winner, and charges of massive fraud and violence were leveled against the Marcos faction. Marcos’s domestic and international support eroded, and he fled the country on Feb. 25, 1986, eventually obtaining asylum in the United States.

Aquino’s government faced mounting problems, including coup attempts, significant economic difficulties, and pressure to rid the Philippines of the U.S. military presence (the last U.S. bases were evacuated in 1992). In 1990, in response to the demands of the Moros, a partially autonomous Muslim region was created in the far south. In 1992, Aquino declined to run for reelection and was succeeded by her former army chief of staff Fidel Ramos. He immediately launched an economic revitalization plan premised on three policies: government deregulation, increased private investment, and political solutions to the continuing insurgencies within the country. His political program was somewhat successful, opening dialogues with the Marxist and Muslim guerillas. However, Muslim discontent with partial rule persisted, and unrest and violence continued throughout the 1990s. In 1999, Marxist rebels and Muslim separatists formed an alliance to fight the government.

Several natural disasters, including the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo on Luzon and a succession of severe typhoons, slowed the country’s economic progress. However, the Philippines escaped much of the economic turmoil seen in other East Asian nations in 1997 and 1998, in part by following a slower pace of development imposed by the International Monetary Fund. Joseph Marcelo Estrada, a former movie actor, was elected president in 1998, pledging to help the poor and develop the country’s agricultural sector. In 1999 he announced plans to amend the constitution in order to remove protectionist provisions and attract more foreign investment.

Late in 2000, Estrada’s presidency was buffeted by charges that he accepted millions of dollars in payoffs from illegal gambling operations. Although his support among the poor Filipino majority remained strong, many political, business, and church leaders called for him to resign. In Nov., 2000, Estrada was impeached by the house of representatives on charges of graft, but the senate, controlled by Estrada’s allies, provoked a crisis (Jan., 2001) when it rejected examining the president’s bank records. As demonstrations against Estrada mounted and members of his cabinet resigned, the supreme court stripped him of the presidency, and Vice President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was sworn in as Estrada’s successor.

Macapagal-Arroyo was elected president in her own right in May, 2004, but the balloting was marred by violence and irregularities as well as a tedious vote-counting process that was completed six weeks after the election.

Source: The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05.

History of the Philippines

The history of the Philippines is believed to have begun with the arrival of the first humans using rafts or primitive boats, at least 67,000 years ago as the 2007 discovery of Callao Man showed.[1] The first recorded visit from the West is the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, who sighted the island of Samar Island on March 16, 1521 and landed on Homonhon Island (now part of Guiuan, Eastern Samar province) the next day. Homonhon Island is southeast of Samar Island.[2]Before Magellan arrived, Negrito tribes inhabited the isles, who were subsequently joined and largely supplanted by migrating groups of Austronesians. This population had stratified into hunter-gatherer tribes, warrior societies, petty plutocracies and maritime-oriented harbor principalities which eventually grew into kingdoms, rajahnates, principalities, confederations and sultanates. The Philippine islands were greatly influenced by Hindu religions, literature and philosophy from India in the early centuries of the Christian era.[3] States included the Indianized Rajahnate of Butuan and Cebu, the dynasty of Tondo, the august kingdoms of Maysapan and Maynila, the Confederation of Madyaas, the sinified Country of Mai, as well as the Muslim Sultanates of Sulu and Maguindanao. These small maritime states flourished from the 1st millennium.[4][5] These kingdoms traded with what are now called China, India, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia.[6] The remainder of the settlements were independent Barangays allied with one of the larger states.

Spanish colonization and settlement began with the arrival of Miguel López de Legazpi's expedition on February 13, 1565 who established the first permanent settlement of San Miguel on the island of Cebu.[7] The expedition continued northward reaching the bay of Manila on the island of Luzon on June 24, 1571,[8] where they established a new town and thus began an era of Spanish colonization that lasted for more than three centuries.[9]

Spanish rule achieved the political unification of almost the whole archipelago, that previously had been composed by independent kingdoms, pushing back south the advancing Islamic forces and creating the first draft of the nation that was to be known as the Philippines. Spain also introduced Christianity, the code of law and the oldest modern Universities in Asia.

The Spanish East Indies were ruled as part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and administered from Mexico City from 1565 to 1821, and administered directly from Madrid, Spain from 1821 until the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898, except for a brief period of British rule from 1762 to 1764. They founded schools, a university, and some hospitals, principally in Manila and the largest Spanish fort settlements. Universal education was made free for all Filipino subjects in 1863 and remained so until the end of the Spanish colonial era. This measure was at the vanguard of contemporary Asian countries, and led to an important class of educated natives, like José Rizal. Ironically, it was during the initial years of American occupation in the early 20th century, that Spanish literature and press flourished.

The Philippine Revolution against Spain began in August 1896, culminating the establishment of the First Philippine Republic. However, the Treaty of Paris, at the end of the Spanish–American War, transferred control of the Philippines to the United States. This agreement was not recognized by the insurgent First Philippine Republic Government which, on June 2, 1899, proclaimed a Declaration of War against the United States.[10] The Philippine–American War which ensued resulted in massive casualties.[11] Philippine president Emilio Aguinaldo was captured in 1901 and the U.S. government declared the conflict officially over in 1902.

The U.S. had established a military government in the Philippines on August 14, 1898, following the capture of Manila.[12] Civil government was inaugurated on July 1, 1901.[13] An elected Philippine Assembly was convened in 1907 as the lower house of a bicameral legislature.[13] Commonwealth status was granted in 1935, preparatory to a planned full independence from the United States in 1946.[14] Preparation for a fully sovereign state was interrupted by the Japanese occupation of the islands during World War II.[15] After the end of the war, the Treaty of Manila established the Philippine Republic as an independent nation.[16]

With a promising economy in the 1950s and 1960s, the Philippines in the late 1960s and early 1970s saw a rise of student activism and civil unrest against President Ferdinand Marcos who declared martial law in 1972.[citation needed] The peaceful and bloodless People Power Revolution of 1986, however, brought about the ousting of Marcos and a return to democracy for the country. The period since then was marked by political instability and hampered economic productivity. However, economic growth has gained pace in recent years to become one of the highest in Asia; as such the Philippines has been labeled one of the Next Eleven countries due to promising future growth.

Prehistory

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Main article: Prehistory of the Philippines

The earliest archeological evidence for man in the archipelago is the 67,000-year-old Callao Man of Cagayan and the Angono Petroglyphs in Rizal, both of whom appear to suggest the presence of human settlement prior to the arrival of the Negritos and Austronesian speaking people.[17][18][19][20][21]There are several opposing theories regarding the origins of ancient Filipinos. F. Landa Jocano theorizes that the ancestors of the Filipinos evolved locally. Wilhelm Solheim's Island Origin Theory[22] postulates that the peopling of the archipelago transpired via trade networks originating in the Sundaland area around 48,000 to 5000 BCE rather than by wide-scale migration. The Austronesian Expansion Theory states that Malayo-Polynesians coming from Taiwan began migrating to the Philippines around 4000 BCE, displacing earlier arrivals.[23][24]

The Negritos were early settlers, but their appearance in the Philippines has not been reliably dated.[25] They were followed by speakers of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, a branch of the Austronesian languages, who began to arrive in successive waves beginning about 4000 BC, displacing the earlier arrivals.[26][27] Before the expansion out of Taiwan, recent archaeological, linguistic and genetic evidence has linked Austronesian speakers in Insular Southeast Asia to cultures such as the Hemudu and Dapenkeng in Neolithic China.[28][29][30][31][32][33]

By 1000 BC the inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago had developed into four distinct kinds of peoples: tribal groups, such as the Aetas, Hanunoo, Ilongots and the Mangyan who depended on hunter-gathering and were concentrated in forests; warrior societies, such as the Isneg and Kalinga who practiced social ranking and ritualized warfare and roamed the plains; the petty plutocracy of the Ifugao Cordillera Highlanders, who occupied the mountain ranges of Luzon; and the harbor principalities of the estuarine civilizations that grew along rivers and seashores while participating in trans-island maritime trade.[34]

Around 300–700 CE the seafaring peoples of the islands traveling in balangays began to trade with the Indianized kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago and the nearby East Asian principalities, adopting influences from both Buddhism and Hinduism.[35][36][unreliable source?]

Classical States (900 AD to 1535)

Main article: History of the Philippines (900–1521)

Initial recorded history

During the period of the south Indian Pallava dynasty and the north Indian Gupta Empire Indian culture spread to Southeast Asia and the Philippines which led to the establishment of Indianized kingdoms.[37][38] The end of Philippine prehistory is 900 CE,[39] the date inscribed in the oldest Philippine document found so far, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. From the details of the document, written in Kawi script, the bearer of a debt, Namwaran, along with his children Lady Angkatan and Bukah, are cleared of a debt by the ruler of Tondo. From the various Sanskrit terms and titles seen in the document, the culture and society of Manila Bay was that of a Hindu–Old Malay amalgamation, similar to the cultures of Java, Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra at the time. There are no other significant documents from this period of pre-Hispanic Philippine society and culture until the Doctrina Christiana of the late 16th century, written at the start of the Spanish period in both native Baybayin script and Spanish. Other artifacts with Kawi script and baybayin were found, such as an Ivory seal from Butuan dated to the early 11th century[40] and the Calatagan pot with baybayin inscription, dated to the 13th century.[41]In the years leading up to 1000 CE, there were already several maritime societies existing in the islands but there was no unifying political state encompassing the entire Philippine archipelago. Instead, the region was dotted by numerous semi-autonomous barangays (settlements ranging in size from villages to city-states) under the sovereignty of competing thalassocracies ruled by datus, rajahs or sultans[42] or by upland agricultural societies ruled by "petty plutocrats". States such as the Kingdom of Maynila, the Kingdom of Taytay in Palawan (mentioned by Pigafetta to be where they resupplied when the remaining ships escaped Cebu after Magellan was slain), the Chieftaincy of Coron Island ruled by fierce warriors called Tagbanua as reported by Spanish missionaries mentioned by Nilo S. Ocampo,[43] Namayan, the Dynasty of Tondo, the Confederation of Madyaas, the rajahnates of Butuan and Cebu and the sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu existed alongside the highland societies of the Ifugao and Mangyan.[44][45][46][47] Some of these regions were part of the Malayan empires of Srivijaya, Majapahit and Brunei.[48][49][50]

The Kingdom of Tondo

Main article: Kingdom of Tondo

The Rajahnate of Butuan

Main article: Kingdom of Butuan

By year 1011 Rajah Sri Bata Shaja, the monarch of the Indianized Rajahnate of Butuan, a maritime-state famous for its goldwork[52]

sent a trade envoy under ambassador Likan-shieh to the Chinese Imperial

Court demanding equal diplomatic status with other states.[53]

The request being approved, it opened up direct commercial links with

the Rajahnate of Butuan and the Chinese Empire thereby diminishing the

monopoly on Chinese trade previously enjoyed by their rivals the Dynasty of Tondo and the Champa civilization.[54] Evidence of the existence of this rajahnate is given by the Butuan Silver Paleograph.[55]

A golden statuette of the Hindu-Buddhist goddess "Kinari" found in an archeological dig in Esperanza, Agusan del Sur.

The Rajahnate of Cebu

Main article: Rajahnate of Cebu

The Rajahnate of Cebu was a classical Philippine state which used to

exist on Cebu island prior to the arrival of the Spanish. It was founded

by Sri Lumay otherwise known as Rajamuda Lumaya, a minor prince of the Chola dynasty which happened to occupy Sumatra. He was sent by the maharajah

to establish a base for expeditionary forces to subdue the local

kingdoms but he rebelled and established his own independent Rajahnate

instead. This rajahnate warred against the 'magalos' (Slave traders) of Maguindanao and had an alliance with the Butuan Rajahnate before it was weakened by the insurrection of Datu (Lord) Lapulapu.[56]The Confederation of Madja-as

Main article: Confederation of Madja-as

Left to right: [1] Images from the Boxer Codex illustrating an ancient kadatuan or tumao (noble class) Visayan couple, [2] a royal couple of the Visayans and [3] a Visayan princess.

The Country of Mai

Main article: Country of Mai

Around 1225, the Country of Mai, a Sinified pre-Hispanic Philippine island-state centered in Mindoro,[59] flourished as an entrepot, attracting traders & shipping from the Kingdom of Ryukyu to the Yamato Empire of Japan.[60] Chao Jukua, a customs inspector in Fukien province, China wrote the Zhufan Zhi ("Description of the Barbarous Peoples"[61]), which described trade with this pre-colonial Philippine state.[62]The Sultanate of Lanao

The Sultanates of Lanao in Mindanao, Philippines were founded in the 16th century through the influence of Shariff Kabungsuan, who was enthroned as first Sultan of Maguindanao in 1520. The Maranaos of Lanao were acquainted with the sultanate system when Islam was introduced to the area by Muslim missionaries and traders from the Middle East, Indian and Malay regions who propagated Islam to Sulu and Maguindanao. Unlike in Sulu and Maguindanao, the Sultanate system in Lanao was uniquely decentralized. The area was divided into Four Principalities of Lanao or the Pat a Pangampong a Ranao which are composed of a number of royal houses (Sapolo ago Nem a Panoroganan or The Sixteen (16) Royal Houses) with specific territorial jurisdictions within mainland Mindanao. This decentralized structure of royal power in Lanao was adopted by the founders, and maintained up to the present day, in recognition of the shared power and prestige of the ruling clans in the area, emphasizing the values of unity of the nation (kaiisaisa o bangsa), patronage (kaseselai) and fraternity (kapapagaria)

Main article: Confederation of sultanates in Lanao

The Sultanate of Sulu

Main article: Sultanate of Sulu

The official flag of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu under the guidance of Ampun Sultan Muedzul Lail Tan Kiram of Sulu.

The Sultanate of Maguindanao

Main article: Sultanate of Maguindanao

At the end of the 15th century, Shariff Mohammed Kabungsuwan of Johor

introduced Islam in the island of Mindanao and he subsequently married

Paramisuli, an Iranun Princess from Mindanao, and established the Sultanate of Maguindanao.[64] By the 16th century, Islam had spread to other parts of the Visayas and Luzon.The expansion of Islam

Spanish settlement and rule (1565–1898)

Main article: History of the Philippines (1521–1898)

Early Spanish expeditions and conquests

Main article: Spanish-Moro Conflict

Over the next several decades, other Spanish expeditions were dispatched to the islands. In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos led an expedition to the islands and gave the name Las Islas Filipinas (after Philip II of Spain) to the islands of Samar and Leyte.[71] The name was extended to the entire archipelago in the twentieth century.

A late 17th-century manuscript by Gaspar de San Agustin from the Archive of the Indies, depicting López de Legazpi's conquest of the Philippines

Legazpi built a fort in Maynila and made overtures of friendship to Rajah Lakandula of Tondo, who accepted. However, Maynila's former ruler, Rajah Sulaiman, refused to submit to Legazpi, but failed to get the support of Lakandula or of the Pampangan and Pangasinan settlements to the north. When Sulaiman and a force of Filipino warriors attacked the Spaniards in the battle of Bangcusay, he was finally defeated and killed.

In 1587, Magat Salamat, one of the children of Lakan Dula, Lakan Dula's nephew, and the lords of the neighboring areas of Tondo, Pandacan, Marikina, Candaba, Navotas and Bulacan were executed when the Tondo Conspiracy of 1587–1588 failed[74] in which a planned grand alliance with the Japanese admiral Gayo, Butuan's last rajah and Brunei's Sultan Bolkieh, would have restored the old aristocracy. Its failure resulted in the hanging of Agustín de Legazpi (great grandson of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi and the initiator of the plot) and the execution of Magat Salamat (the crown-prince of Tondo).[75]

Spanish power was further consolidated after Miguel López de Legazpi's conquest of the Confederation of Madya-as, his subjugation of Rajah Tupas, the King of Cebu and Juan de Salcedo's conquest of the provinces of Zambales, La Union, Ilocos, the coast of Cagayan, and the ransacking of the Chinese warlord Limahong's pirate kingdom in Pangasinan.

The Spanish and the Moros also waged many wars over hundreds of years in the Spanish-Moro Conflict, not until the 19th century did Spain succeed in defeating the Sulu Sultanate and taking Mindanao under nominal suzerainty.

Spanish settlement during the 16th and 17th centuries

The "Memoria de las Encomiendas en las Islas" of 1591, just twenty years after the conquest of Luzon, reveals a remarkable[according to whom?] progress in the work of colonization and the spread of Christianity. A cathedral was built in the city of Manila with an episcopal palace, Augustinian, Dominican and Franciscan monasteries and a Jesuit house. The king maintained a hospital for the Spanish settlers and there was another hospital for the natives run by the Franciscans. The garrison was composed of roughly two hundred soldiers. In the suburb of Tondo there was a convent run by Franciscan friars and another by the Dominicans that offered Christian education to the Chinese converted to Christianity. The same report reveals that in and around Manila were collected 9,410 tributes, indicating a population of about 30,640 who were under the instruction of thirteen missionaries (ministers of doctrine), apart from the monks in monasteries. In the former province of Pampanga the population estimate was 74,700 and 28 missionaries. In Pangasinan 2,400 people with eight missionaries. In Cagayan and islands Babuyanes 96,000 people but no missionaries. In La Laguna 48,400 people with 27 missionaries. In Bicol and Camarines Catanduanes islands 86,640 people with fifteen missionaries. The total was 667,612 people under the care of 140 missionaries, of which 79 were Augustinians, nine Dominicans and 42 Franciscans.[76]The fragmented nature of the islands made it easy for Spanish colonization. The Spanish then brought political unification to most of the Philippine archipelago via the conquest of the various states although they were unable to fully incorporate parts of the sultanates of Mindanao and the areas where tribes and highland plutocracy of the Ifugao of Northern Luzon were established. The Spanish introduced elements of western civilization such as the code of law, western printing and the Gregorian calendar alongside new food resources such as maize, pineapple and chocolate from Latin America.[77]

Outside the tertiary institutions, the efforts of missionaries were in no way limited to religious instruction but also geared towards promoting social and economic advancement of the islands. They cultivated into the natives their innate[citation needed] taste for music and taught Spanish language to children.[79] They also introduced advances in rice agriculture, brought from America corn and cocoa and developed the farming of indigo, coffee and sugar cane. The only commercial plant introduced by a government agency was the plant of tobacco.

Church and state were inseparably linked in Spanish policy, with the state assuming responsibility for religious establishments.[80] One of Spain's objectives in colonizing the Philippines was the conversion of the local population to Roman Catholicism. The work of conversion was facilitated by the absence of other organized religions, except for Islam, which was still predominant in the southwest. The pageantry of the church had a wide appeal, reinforced by the incorporation of indigenous social customs into religious observances.[80] The eventual outcome was a new Roman Catholic majority, from which the Muslims of western Mindanao and the upland tribal peoples of Luzon remained detached and alienated (such as the Ifugaos of the Cordillera region and the Mangyans of Mindoro).[80]

At the lower levels of administration, the Spanish built on traditional village organization by co-opting local leaders. This system of indirect rule helped create an indigenous upper class, called the principalía, who had local wealth, high status, and other privileges. This perpetuated an oligarchic system of local control. Among the most significant changes under Spanish rule was that the indigenous idea of communal use and ownership of land was replaced with the concept of private ownership and the conferring of titles on members of the principalia.[80]

Around 1608 William Adams, an English navigator contacted the interim governor of the Philippines, Rodrigo de Vivero y Velasco on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who wished to establish direct trade contacts with New Spain. Friendly letters were exchanged, officially starting relations between Japan and New Spain. From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as a territory of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from Mexico, via the Royal Audiencia of Manila, and administered directly from Spain from 1821 after the Mexican revolution,[81] until 1898.

Many of the Aztec and Mayan warriors that López de Legazpi brought with him eventually settled in Mexico, Pampanga where traces of Aztec and Mayan influence can still be found in the many chico plantations in the area (chico is a fruit indigenous only to Mexico) and also by the name of the province itself.[82]

The Manila galleons which linked Manila to Acapulco traveled once or twice a year between the 16th and 19th centuries. The Spanish military fought off various indigenous revolts and several external colonial challenges, especially from the British, Chinese pirates, Dutch, and Portuguese. Roman Catholic missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to Christianity and founded schools, universities, and hospitals. In 1863 a Spanish decree introduced education, establishing public schooling in Spanish.[83]

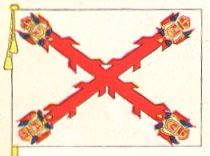

Coat of arms of Manila were at the corners of the Cross of Burgundy in the Spanish-Filipino battle standard.

Spanish rule during the 18th century

Colonial income derived mainly from entrepôt trade: The Manila Galleons sailing from the Fort of Manila to the Fort of Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico brought shipments of silver bullion, and minted coin that were exchanged for return cargoes of Asian, and Pacific products. A total of 110 Manila galleons set sail in the 250 years of the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade (1565 to 1815). There was no direct trade with Spain until 1766.[80]The Philippines was never profitable as a colony during Spanish rule, and the long war against the Dutch in the 17th century together with the intermittent conflict with the Muslims in the South nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.[80] The Royal Fiscal of Manila wrote a letter to King Charles III of Spain, in which he advises to abandon the colony.

The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy paid by the Spanish Crown, and the 200-year-old fortifications at Manila had not been improved much since first built by the early Spanish colonizers.[84] This was one of the circumstances that made possible the brief British occupation of Manila between 1762 and 1764.

British invasion (1762–1764)

Main article: British occupation of Manila

Britain declared war against Spain on January 4, 1762 and on September 24, 1762 a force of British Army regulars and British East India Company soldiers, supported by the ships and men of the East Indies Squadron of the British Royal Navy, sailed into Manila Bay from Madras, India.[85] Manila fell to the British on October 4, 1762.The British forces were confined to Manila and the nearby port of Cavite by the resistance organised by the provisional Spanish colonial government. Suffering a breakdown of command and troop desertions as a result of their failure to secure control of the Philippines, the British ended their occupation of Manila by sailing away in April 1764 as agreed to in the peace negotiations in Europe. The Spaniards then persecuted the Binondo Chinese community for its role in aiding the British.

Spanish rule in the second part of the 18th century

In 1781, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas established the Economic Society of the Friends of the Country.[86] The Philippines was administered from the Viceroyalty of New Spain until the grant of independence to Mexico in 1821 necessitated the direct rule from Spain of the Philippines from that year.

Spanish rule during the 19th century

During the 19th century Spain invested heavily in education and infrastructure. Through the Education Decree of December 20, 1863, Queen Isabella II of Spain decreed the establishment of a free public school system that used Spanish as the language of instruction, leading to increasing numbers of educated Filipinos.[87] Additionally, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 cut travel time to Spain, which facilitated the rise of the ilustrados, an enlightened class of Filipinos that had been able to expand their studies in Spain and Europe.Spanish Manila was seen in the 19th century as a model of colonial governance that effectively put the interests of the original inhabitants of the islands before those of the colonial power. As John Crawfurd put it in its History of the Indian Archipelago, in all of Asia the "Philippines alone did improve in civilization, wealth, and populousness under the colonial rule" of a foreign power.[89] John Bowring, Governor General of British Hong Kong from 1856 to 1860, wrote after his trip to Manila:

Credit is certainly due to Spain for having bettered the condition of a people who, though comparatively highly civilized, yet being continually distracted by petty wars, had sunk into a disordered and uncultivated state.In The inhabitants of the Philippines, Frederick Henry Sawyer wrote:

The inhabitants of these beautiful Islands upon the whole, may well be considered to have lived as comfortably during the last hundred years, protected form all external enemies and governed by mild laws vis-a-vis those from any other tropical country under native or European sway, owing in some measure, to the frequently discussed peculiar (Spanish) circumstances which protect the interests of the natives.[90]

Until an inept bureaucracy was substituted for the old paternal rule, and the revenue quadrupled by increased taxation, the Filipinos were as happy a community as could be found in any colony. The population greatly multiplied; they lived in competence, if not in affluence; cultivation was extended, and the exports steadily increased. Let us be just; what British, French, or Dutch colony, populated by natives can compare with the Philippines as they were until 1895?."[91]The first official census in the Philippines was carried out in 1878. The colony's population as of December 31, 1877, was recorded at 5,567,685 persons.[92] This was followed by the 1887 census that yielded a count of 6,984,727,[93] while that of 1898 yielded 7,832,719 inhabitants .[94]

The estimated GDP per capita for the Philippines in 1900, the year Spain left, was of $1,033.00. That made it the second richest place in all of Asia, just a little behind Japan ($1,135.00), and far ahead of China ($652.00) or India ($625.00).[95]

Philippine Revolution

Main article: Philippine Revolution

Revolutionary sentiments arose in 1872 after three Filipino priests, Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, known as Gomburza, were accused of sedition by colonial authorities and executed. This would inspire the Propaganda Movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, Graciano López Jaena, and Mariano Ponce, that clamored for adequate representation to the Spanish Cortes and later for independence. José Rizal, the most celebrated intellectual and radical ilustrado of the era, wrote the novels "Noli Me Tángere", and "El filibusterismo", which greatly inspired the movement for independence.[96] The Katipunan, a secret society whose primary purpose was that of overthrowing Spanish rule in the Philippines, was founded by Andrés Bonifacio who became its Supremo (leader).The Philippine Revolution began in 1896. Rizal was wrongly implicated in the outbreak of the revolution and executed for treason in 1896. The Katipunan in Cavite split into two groups, Magdiwang, led by Mariano Álvarez (a relative of Bonifacio's by marriage), and Magdalo, led by Emilio Aguinaldo. Leadership conflicts between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo culminated in the execution or assassination of the former by the latter's soldiers. Aguinaldo agreed to a truce with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato and Aguinaldo and his fellow revolutionaries were exiled to Hong Kong. Not all the revolutionary generals complied with the agreement. One, General Francisco Makabulos, established a Central Executive Committee to serve as the interim government until a more suitable one was created. Armed conflicts resumed, this time coming from almost every province in Spanish-governed Philippines.

In 1898, as conflicts continued in the Philippines, the USS Maine, having been sent to Cuba because of U.S. concerns for the safety of its citizens during an ongoing Cuban revolution, exploded and sank in Havana harbor. This event precipitated the Spanish–American War.[97] After Commodore George Dewey defeated the Spanish squadron at Manila, a German squadron arrived in Manila and engaged in maneuvers which Dewey, seeing this as obstruction of his blockade, offered war—after which the Germans backed down.[98] The German Emperor expected an American defeat, with Spain left in a sufficiently weak position for the revolutionaries to capture Manila—leaving the Philippines ripe for German picking.[99]

The U.S. invited Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines in the hope he would rally Filipinos against the Spanish colonial government. Aguinaldo arrived on May 19, 1898, via transport provided by Dewey. By the time U.S. land forces had arrived, the Filipinos had taken control of the entire island of Luzon, except for the walled city of Intramuros. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the independence of the Philippines in Kawit, Cavite, establishing the First Philippine Republic under Asia's first democratic constitution.[96]

In the Battle of Manila, the United States captured the city from the Spanish. This battle marked an end of Filipino-American collaboration, as Filipino forces were prevented from entering the captured city of Manila, an action deeply resented by the Filipinos.[100] Spain and the United States sent commissioners to Paris to draw up the terms of the Treaty of Paris which ended the Spanish–American War. The Filipino representative, Felipe Agoncillo, was excluded from sessions as the revolutionary government was not recognized by the family of nations.[100] Although there was substantial domestic opposition, the United States decided to annex the Philippines. In addition to Guam and Puerto Rico, Spain was forced in the negotiations to hand over the Philippines to the U.S. in exchange for US$20,000,000.00.[101] U.S. President McKinley justified the annexation of the Philippines by saying that it was "a gift from the gods" and that since "they were unfit for self-government, ... there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them",[102][103] in spite of the Philippines having been already Christianized by the Spanish over the course of several centuries. It is also in spite of the Spanish having created the first public education system in Asia (public education decree of 1863) and the first universities in the continent: University of Santo Tomas in 1611, and University of San Carlos (Cebu) in 1595. It was also clearly a misrepresentation to state that the Philippines needed to be "civilized". The archipelago saw rapid growth and development during Spanish rule thanks to the introduction of many elements of Western civilization, including irrigation, the plow and the wheel, new construction and engineering methods, factories, modern hospitals, the telephone and the telegraph, railroads and public lighting. By 1898 the Philippines was one of the most advanced countries in Asia, producing great statesmen, writers and scientists such as national hero José Rizal.

The first Philippine Republic resisted the U.S. occupation, resulting in the Philippine–American War (1899–1913).

American rule (1898–1946)

Main article: History of the Philippines (1898-1946)

1898 political cartoon showing U.S. President McKinley with a native child. Here, returning the Philippines to Spain is compared to throwing the child off a cliff.

Philippine–American War

Main article: Philippine–American War

Hostilities broke out on February 4, 1899, after two American privates on patrol killed three Filipino soldiers in San Juan, a Manila suburb.[106] This incident sparked the Philippine–American War, which would cost far more money and took far more lives than the Spanish–American War.[96] Some 126,000 American soldiers would be committed to the conflict; 4,234 Americans died, as did 12,000–20,000 Philippine Republican Army soldiers who were part of a nationwide guerrilla movement of indeterminate numbers.[106]The general population, caught between Americans and rebels, suffered significantly. At least 200,000 Filipino civilians lost their lives as an indirect result of the war mostly as a result of the cholera epidemic at the war's end that took between 150,000 and 200,000 lives.[107] Atrocities were committed by both sides.[106]

The poorly equipped Filipino troops were easily overpowered by American troops in open combat, but they were formidable opponents in guerrilla warfare.[106] Malolos, the revolutionary capital, was captured on March 31, 1899. Aguinaldo and his government escaped, however, establishing a new capital at San Isidro, Nueva Ecija. On June 5, 1899, Antonio Luna, Aguinaldo's most capable military commander, was killed by Aguinaldo's guards in an apparent assassination while visiting Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija to meet with Aguinaldo.[108] With his best commander dead and his troops suffering continued defeats as American forces pushed into northern Luzon, Aguinaldo dissolved the regular army on November 13 and ordered the establishment of decentralized guerrilla commands in each of several military zones.[109] Another key general, Gregorio del Pilar, was killed on December 2, 1899 in the Battle of Tirad Pass—a rear guard action to delay the Americans while Aguinaldo made good his escape through the mountains.

Aguinaldo was captured at Palanan, Isabela on March 23, 1901 and was brought to Manila. Convinced of the futility of further resistance, he swore allegiance to the United States and issued a proclamation calling on his compatriots to lay down their arms, officially bringing an end to the war.[106] However, sporadic insurgent resistance continued in various parts of the Philippines, especially in the Muslim south, until 1913.[110]

In 1900, President McKinley sent the Taft Commission, to the Philippines, with a mandate to legislate laws and re-engineer the political system.[111] On July 1, 1901, William Howard Taft, the head of the commission, was inaugurated as Civil Governor, with limited executive powers.[112] The authority of the Military Governor was continued in those areas where the insurrection persisted.[113] The Taft Commission passed laws to set up the fundamentals of the new government, including a judicial system, civil service, and local government. A Philippine Constabulary was organized to deal with the remnants of the insurgent movement and gradually assume the responsibilities of the United States Army.[114]

The Tagalog, Negros and Zamboanga Cantonal Republics

During the First Philippine Republic, three other insurgent republics were briefly formed: the Tagalog Republic in Luzon, under Macario Sakay,[115] the Negros Republic in the Visayas under Aniceto Lacson, and the Republic of Zamboanga in Mindanao under Mariano Arquiza.[116] Despite resistance from these three republics ignored by Aguinaldo who included them in his gift to the USA, all three were eventually dissolved and the Philippines was ruled as a singular insular territory.Insular Government (1901–1935)

Main article: Insular Government of the Philippine Islands

The Philippine Organic Act was the basic law for the Insular Government, so called because civil administration was under the authority of the U.S. Bureau of Insular Affairs. This government saw its mission as one of tutelage, preparing the Philippines for eventual independence.[117] On July 4, 1902 the office of military governor was abolished and full executive power passed from Adna Chaffee, the last military governor, to Taft, who became the first U.S. governor-general of the Philippines.[118]In socio-economic terms, the Philippines made solid progress in this period. Foreign trade had amounted to 62 million pesos in 1895, 13% of which was with the United States. By 1920, it had increased to 601 million pesos, 66% of which was with the United States.[119] A health care system was established which, by 1930, reduced the mortality rate from all causes, including various tropical diseases, to a level similar to that of the United States itself. The practices of slavery, piracy and headhunting were suppressed but not entirely extinguished.

A new educational system was established with English as the medium of instruction, eventually becoming a lingua franca of the Islands. The 1920s saw alternating periods of cooperation and confrontation with American governors-general, depending on how intent the incumbent was on exercising his powers vis-à-vis the Philippine legislature. Members to the elected legislature lobbied for immediate and complete independence from the United States. Several independence missions were sent to Washington, D.C. A civil service was formed and was gradually taken over by Filipinos, who had effectively gained control by 1918.

Philippine politics during the American territorial era was dominated by the Nacionalista Party, which was founded in 1907. Although the party's platform called for "immediate independence", their policy toward the Americans was highly accommodating.[120] Within the political establishment, the call for independence was spearheaded by Manuel L. Quezon, who served continuously as Senate president from 1916 until 1935.

World War I gave the Philippines the opportunity to pledge assistance to the US war effort. This took the form of an offer to supply a division of troops, as well as providing funding for the construction of two warships. A locally recruited national guard was created and significant numbers of Filipinos volunteered for service in the US Navy and army.[121]

Frank Murphy was the last Governor-General of the Philippines (1933–35), and the first U.S. High Commissioner of the Philippines (1935–36). The change in form was more than symbolic: it was intended as a manifestation of the transition to independence.

Commonwealth

Main article: Commonwealth of the Philippines

Commonwealth President Manuel L. Quezon with United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, D.C.

A Constitutional Convention was convened in Manila on July 30, 1934. On February 8, 1935, the 1935 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines was approved by the convention by a vote of 177 to 1. The constitution was approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 23, 1935 and ratified by popular vote on May 14, 1935.[125][126]

On September 17, 1935,[127] presidential elections were held. Candidates included former president Emilio Aguinaldo, the Iglesia Filipina Independiente leader Gregorio Aglipay, and others. Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña of the Nacionalista Party were proclaimed the winners, winning the seats of president and vice-president, respectively.[128]

The Commonwealth Government was inaugurated on the morning of November 15, 1935, in ceremonies held on the steps of the Legislative Building in Manila. The event was attended by a crowd of around 300,000 people.[127] Under the Tydings–McDuffie Act this meant that the date of full independence for the Philippines was set for July 4, 1946, a timetable which was followed after the passage of almost eleven very eventful years.

World War II and Japanese occupation

Main articles: Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Second Philippine Republic and Home front during World War II § The Philippines

Military

Japan launched a surprise attack on the Clark Air Base in Pampanga on the morning of December 8, 1941, just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Aerial bombardment was followed by landings of ground troops on Luzon. The defending Philippine and United States troops were under the command of General Douglas MacArthur. Under the pressure of superior numbers, the defending forces withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and to the island of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay.On January 2, 1942, General MacArthur declared the capital city, Manila, an open city to prevent its destruction.[129] The Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of United States-Philippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and on Corregidor in May of the same year. Most of the 80,000 prisoners of war captured by the Japanese at Bataan were forced to undertake the infamous Bataan Death March to a prison camp 105 kilometers to the north. About 10,000 Filipinos and 1,200 Americans died before reaching their destination.[130]

President Quezon and Osmeña had accompanied the troops to Corregidor and later left for the United States, where they set up a government in exile.[131] MacArthur was ordered to Australia, where he started to plan for a return to the Philippines.

The Japanese military authorities immediately began organizing a new government structure in the Philippines and established the Philippine Executive Commission. They initially organized a Council of State, through which they directed civil affairs until October 1943, when they declared the Philippines an independent republic. The Japanese-sponsored republic headed by President José P. Laurel proved to be unpopular.[132]

Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by large-scale underground and guerrilla activity. The Philippine Army, as well as remnants of the U.S. Army Forces Far East,[133][134] continued to fight the Japanese in a guerrilla war and was considered an auxiliary unit of the United States Army.[135] Their effectiveness was such that by the end of the war, Japan controlled only twelve of the forty-eight provinces.[132] One element of resistance in the Central Luzon area was furnished by the Hukbalahap, which armed some 30,000 people and extended their control over much of Luzon.[132]

The occupation of the Philippines by Japan ended at the war's conclusion. The American army had been fighting the Philippines Campaign since October 1944, when MacArthur's Sixth United States Army landed on Leyte. Landings in other parts of the country had followed, and the Allies, with the Philippine Commonwealth troops, pushed toward Manila. However, fighting continued until Japan's formal surrender on September 2, 1945. Approximately 10,000 U.S. soldiers were missing in action in the Philippines when the war ended, more than in any other country in the Pacific or European Theaters. The Philippines suffered great loss of life and tremendous physical destruction, specially during the Battle of Manila. An estimated 1 million Filipinos had been killed, a large portion during the final months of the war, and Manila had been extensively damaged.[132]

Home front

As in most occupied countries, crime, looting, corruption, and black markets were endemic. Japan in 1943 proposed independence on new terms, and some collaborators went along with the plan, but Japan was clearly losing the war and nothing became of it.[136]With a view of building up the economic base of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, the Japanese Army envisioned using the islands as a source of agricultural products needed by its industry. For example Japan had a surplus of sugar from Taiwan, and a severe shortage of cotton, so they try to grow cotton in on sugar lands with disastrous results. They lacked the seeds, pesticides, and technical skills to grow cotton. Jobless farm workers flock to the cities, where there was minimal relief and few jobs. The Japanese Army also tried using cane sugar for fuel, castor beans and copra for oil, derris for quinine, cotton for uniforms, and abaca (hemp) for rope. The plans were very difficult to implement in the face of limited skills, collapsed international markets, bad weather, and transportation shortages. The program was a failure that gave very little help to Japanese industry, and diverted resources needed for food production.[137] As Karnow reports, Filipinos "rapidly learned as well that 'co-prosperity' meant servitude to Japan's economic requirements." [138]

Living conditions were bad throughout the Philippines during the war. Transportation between the islands was difficult because of lack of fuel. Food was in very short supply, with sporadic famines and epidemic diseases.[139]

Independent Philippines and the Third Republic (1946–1975)

Main article: History of the Philippines (1946–1965)

Administration of Manuel Roxas (1946–1948)

Administration of Elpidio Quirino (1948–1953)

World War II had left the Philippines demoralized and severely damaged. The task of reconstruction was complicated by the activities of the Communist-supported Hukbalahap guerrillas (known as "Huks"), who had evolved into a violent resistance force against the new Philippine government. Government policy towards the Huks alternated between gestures of negotiation and harsh suppression. Secretary of Defense Ramon Magsaysay initiated a campaign to defeat the insurgents militarily and at the same time win popular support for the government. The Huk movement had waned in the early 1950s, finally ending with the unconditional surrender of Huk leader Luis Taruc in May 1954.

Administration of Ramon Magsaysay (1953–1957)

Administration of Carlos P. Garcia (1957–1961)

Administration of Diosdado Macapagal (1961–1965)

Land Reform Code

Main article: Agricultural Land Reform Code

No comments:

Post a Comment